|

(Chapter II, section 7)

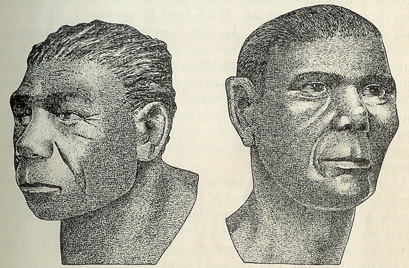

Chronological and Geographical Differentiation of the European Aurignacian group The Aurignacian flake culture,31 with which the Upper Palaeolithic period in Europe began, was not a single unit throughout its time span, but seems to have been composed of several separate entities derived from more than one non-European source. The first Aurignacian level in Europe, the Chatelperronian, is represented by three skeletons only. These include the two “negroids” from the Grotte des Enfants, Grimaldi, near Mentone, and Combe Capelle. Of the three, the Grimaldi pair may have been the older. Except that they belonged to the earliest Aurignacian period, a more exact estimate of their age is not possible.32 These were the remains of an adult female and an adolescent male. Disregarding for the moment their racial affinities, we may be sure that they were fully sapiens, and that they resembled Galley Hill in stature and in gross cranial vault form. The vault dimensions, however, are smaller. They thus show nothing whatever of the great size and robusticity of the crania belonging to the total Upper Palaeolithic group, and nothing of the latter’s exuberance of bodily growth. In other respects they were apparently somewhat negroid. in the sense that they possessed features divergent from the modern white standard in a modern negroid direction.33 These include the virtual absence of browridges, a sharp bowing of the frontal bone, low, broad nasal bones, a guttered lower border of the nasal opening, alveolar prognathism, a large palate, and large teeth. The orbits, furthermore, are relatively narrow, the face both absolutely short and narrow. The long bones show a difference, however, in limb proportions between these people and Galley Hill, for the distal segments are relatively long, and the arms long in relation to the legs.34 In this as in the possession of long heels35 the Grimaldi specimens are truly negroid, and again upset the unity of the total Upper Palaeolithic sample. There is no type of man more completely sapiens36 than a negro. The two Grimaldi specimens, in being partially negroid variants or relatives of the Galley Hill group, are entirely divorced from the line or evolution which produced either the Palestinian Skhul people or the later European Aurignacians. In this respect the argument as to how much or how little negroid they actually were, is of no importance. Whence they came to Europe, in the van of the Upper Palaeolithic migrations, is likewise not, at the moment, worthy of extensive argument. They must have come from Africa or southwestern Asia, but until others of the same type have been found, the problem will remain open. They may represent an early negro-white mixture, or a generalized proto-negroid in the process of specialization.37 They are probably too late, however, in time, to have been contemporary members of the generalized stock which may have been mutually ancestral to the negroes and whites. The study of the third specimen, the male skeleton of Combe Capelle, is more pertinent to our present problem. Like the two Grimaldi negroids, it deviates completely from the body of Upper Palaeolithic crania and long bones in the distinctive features of the main group. Although as long as the mean for the total series, the cranial vault is considerably narrower, somewhat higher, and smaller in capacity. In the details of vault form, it is essentially similar to Galley Hill, but is actually narrower even than Galley Hill itself. The Combe Capelle face is the earliest which can be definitely associated with a Galley Hill type of vault. Here it differs again from the middle Aurignacians to follow, for the bizygomatic and bigonial diameters are as small as those of most modern long-headed white men, and the face, orbits, and mandible are narrow. The nasal opening is wider than those of most later Upper Palaeolithic European crania hut the nasal bones are European in form. There is no prognathism and the subnasal segment of the face is not exceptionally large. Like Galley Hill, Combe Capelle man was short, with a stature of 1 60—I 62 cm. It will be necessary, in studying the crania of the remainder of the Aurignacian, to combine all sub-periods, since no distinction has been made in the majority of cases. Furthermore, the crania which might have been Solutrean are also included. The present survey, then, includes the famous Crô-Magnons of France, and the Moravian mammoth hunters, who lived in the open and buried their dead in sepulchres built of mammoth jaws and shoulder blades. Despite the general homogeneity of Upper Palaeolithic man, these two groups, the western and eastern, may be shown to have differed from each other in certain well-defined ways. Both were tall, with statures well

Both the western and the eastern type possess the special characteristics of Upper Palaeolithic man which have been described earlier. But there is one principal feature which separates them—the cranial index. The Crô-Magnons, who were concentrated in France, range in this ratio from 69 to 85, whereas the eastern group, including the Russian skulls, ranges from 64 to 76. The mean index for the French skulls equals 76, while that of the eastern group, representing the same period of time, is 71. In other Words, the eastern Aurignacian type, like Galley Hill and Combe Capelle, Was purely dolichocephalic, while the Middle and Late Aurignacians of France include among their numbers a brachycephalic element, which reaches the high limit of 85 in the male skull, Solutré #2. The western group has been named Crô-Magnon after a senile male skull which is usually taken as the standard example of this type, and which possesses the most specialized Upper Palaeolithic features in an exaggerated manner. Skulls of this type have a rather flat vault, the lowest and broadest orbits in the entire. series, and short, extremely wide faces. Their nasal apertures are of medium width, and their nasal bones highly curved and projecting. The most brachycephalic skull shows, of course, quite a different conformation of the cranial vault. It belongs to the curvoccipital type, with a gently rounded rear profile. This Solutré #2 specimen is a large skull, and belonged to a tall man. Its face, however, shows the typical Crô-Magnon features of flaring zygomata and wide jaw, combined with extremely low orbits. The Crô-Magnon character of this face, while marked, is not as clearly shown as in the dolichocephalic examples, for the fuller bulge of the temporals obscures it. The Crô-Magnon type, in the widest sense, therefore, includes both long-headed and round-headed examples with transitions in between, and the features which differentiate it are just as pronounced in the roundest skulls as in the more numerous narrower ones. Let us turn to central and eastern Europe, and study the purely long-headed examples from this part of the continent. In general, they resemble an exaggerated and leptorrhine Combe Capelle, with the low orbits, wide faces, and heavy jaws found in excess further west. A few skulls deviate in various ways from the standard, however; of these three are notable, Brünn #1, Lautsch, and Předmost #3. Brunn #1, which lacks a face, but possesses a mandible, is, in vault form and size, and in the lower jaw, the duplicate of Combe Capelle. Lautsch, which has a face, belongs partly to the same general class, but is broader. Its face, however, is narrow, and in this conforms to the Combe Capelle type. On the whole, the eastern skulls, while subjected to the same influence which brought about an increase in gross size and osseous extravagance in the Crô-Magnons, nevertheless cling closer to the older Galley Hill form, and were not affected by whatever factor caused the brachycephaly in some of the western specimens. The third of the not fully typical eastern crania, Předmost #3,38 is of great value, for it reveals in a certain manner the reason for the general peculiarities of the Upper Palaeolithic series as a whole, and for their separation, shown by Morant, from the bulk of living humanity. This reason is simply that Předmost #3 resembles Skhul #5 very closely, both morphologically and metrically, while neither of these two specimens deviates notably from the Upper Palaeolithic metrical means. On the whole, the Upper Palaeolithic group, including Předmost #3, is intermediate between the Galley Hill-Combe Capelle type and the Neanderthals, as known to us from the European Neanderthaloid group.39 In the first place, the horizontal circumference, taken above the browridges, ranges from 538 to 563 mm. in male Neanderthals. The Upper Palaeolithic means is 549.1 mm., the individual figure of Předmost #3 is 556, that of Combe Capelle, 527 mm., which would be nearer a modern dolichocephalic mean. In face breadth, the Neanderthal figure is represented by La Chapelle aux Saints With 152 mm., and the Le Moustier adolescent with 148 mm. The Upper Palaeolithic mean is 142.8 mm., Předmost #3 is 144 mm., and Combe Capelle 137 mm. Again, Combe Capelle represents modern European man, and the Upper Palaeolithic group takes an intermediate position. The same intermediate position is found in a number of other characters, including the vault breadth and height, the minimum frontal diameter, the widths of the orbits, and the distance between the orbits. In individual cases, such as Předmost #3, the upper face height is intermediate also, but in the group as a whole it is not, for the shorter dimension prevails. The same is true of the nasal dimensions in which Upper Palaeolithic man is not perceptibly Neanderthaloid. The cranial lengths of the Upper Palaeolithic group are no greater than those of Combe Capelle and Galley Hill; in fact, frequently shorter. The reason for this may be that the equivalent Neanderthaloid diameter includes the browridges, which, when eliminated, make the brain length somewhat less than that of Galley Hill. The stature of the Upper Palaeolithic group equals that of Skhul; the sex differentiation in size is the same; the pelves are similar, and so is the rib section. The hands and feet are likewise large. If the European group, with the exception of Předmost #3, is less Neanderthaloid looking than Skhul, this is not surprising. The distance in time between the two was probably as great as or greater than that between the beginning of the Middle Aurignacian and the present. Furthermore, we have been comparing European Upper Palaeolithic skeletons with those of European Neanderthals. While the Aurignacian hunters of Europe may possibly have absorbed some of the local Neanderthal survivors, it is likely that the main accretion of this element took place farther east,40 and we do not know that those so accreted were as specialized in a non-sapiens direction as the European examples. In admitting the partially Neanderthaloid character of Upper Palaeolithic man (which is no new theory), we must accept at the same time some genetic principles which apply to modern primary crosses between distant races,41 as well as to these ancient interspecific mixtures. Although blending is the rule in most characters, simple dominance appears in a few; while major changes in size appear through this mixing. The stature of the hybrids far exceeds that of their parents, and through the general genetic upset, the brain size becomes greater than that of the earlier purely sapiens stock. It must be admitted that there is an alternative interpretation of the Neanderthaloid traits of Upper Palaeolithic man. That is that he represents a stage in the evolution of Neanderthal in a sapiens direction; that different branches of the Neanderthaloid stock evolved into sapiens men at different times; and that the Swanscombe—Galley Hill—Kanam—Kanjera stock went through this process at a much earlier date than did the group under consideration. For the purposes of the present study, it makes no difference whether the early sapiens stock, fully evolved by the Mid-Pleistocene, had passed through a Neanderthaloid stage in its previous history, or had evolved directly from some less gerontomorphic and more gibbonoid ancestor. The question which is at the moment pertinent is, are the Skhul—Upper Palaeolithic peoples to be considered Neanderthaloid-sapiens hybrids, or simply evolved Neanderthaloids, in which case the hybridization connecting the Upper Palaeolithic people with modern Europeans would have occurred later? All of the existing evidence, of somatology as of archaeology, points to the former hypothesis, which we have accepted, in lieu of further information, as one of the main theses in our reconstruction of European racial history. Returning to the specific consideration of the Upper Palaeolithic European group, we find that the difference between the eastern and the western Aurignacians, which consists, most demonstrably, of the brachycephalic tendency in the latter, has not been explained. It might, however, have been due to a differential mixture between sapiens and more than one Neanderthaloid strain. The Neanderthaloids in Europe, who lived in the western part of the continent, varied in cranial index from 67 (Gibraltar) to 77 (La Quina), and were not far from the French Upper Palaeolithic mean of 76. When measured from ophyron, a point on the frontal bone behind the browridges, the crania of these Neanderthals have the following lengths: three males, 193, 186, 187; three females, 185, 183, 186 mm. These are shorter than the French Upper Palaeolithic means, taken from the same point, of 195.6 mm. for males, and 188.6 mm. for females. The cranial indices calculated from these lengths are, in five out of eight Neanderthal cases, above 80.0. Thus there was, in the Neanderthal group as we know it, a brachycranial, or brachycerebral, tendency in brain form which, with a reduction of browridges, might, in mixture, have caused brachycephaly in some of the hybrids. That it may have done so in the case of the French brachycephals, notably Solutré #2, which has a cranial length of 182.5 mm., is by no means more than a suggestion. As the reader will have gathered

from the preceding pages, the study of race in Europe during the advance of

the last ice is not a simple matter, nor one to be solved lightly. It will

be of help to study parallel developments in other quarters, especially in

Africa.

31 Garrod, Miss D. A. E.,

RBAA, Pres. Ad., Sect. H., 1936, pp. 155—172.

|